Aquarium Drunkard Presents: Who Is Harry Nilsson and Why Is Van Dyke Parks Talking About Him?

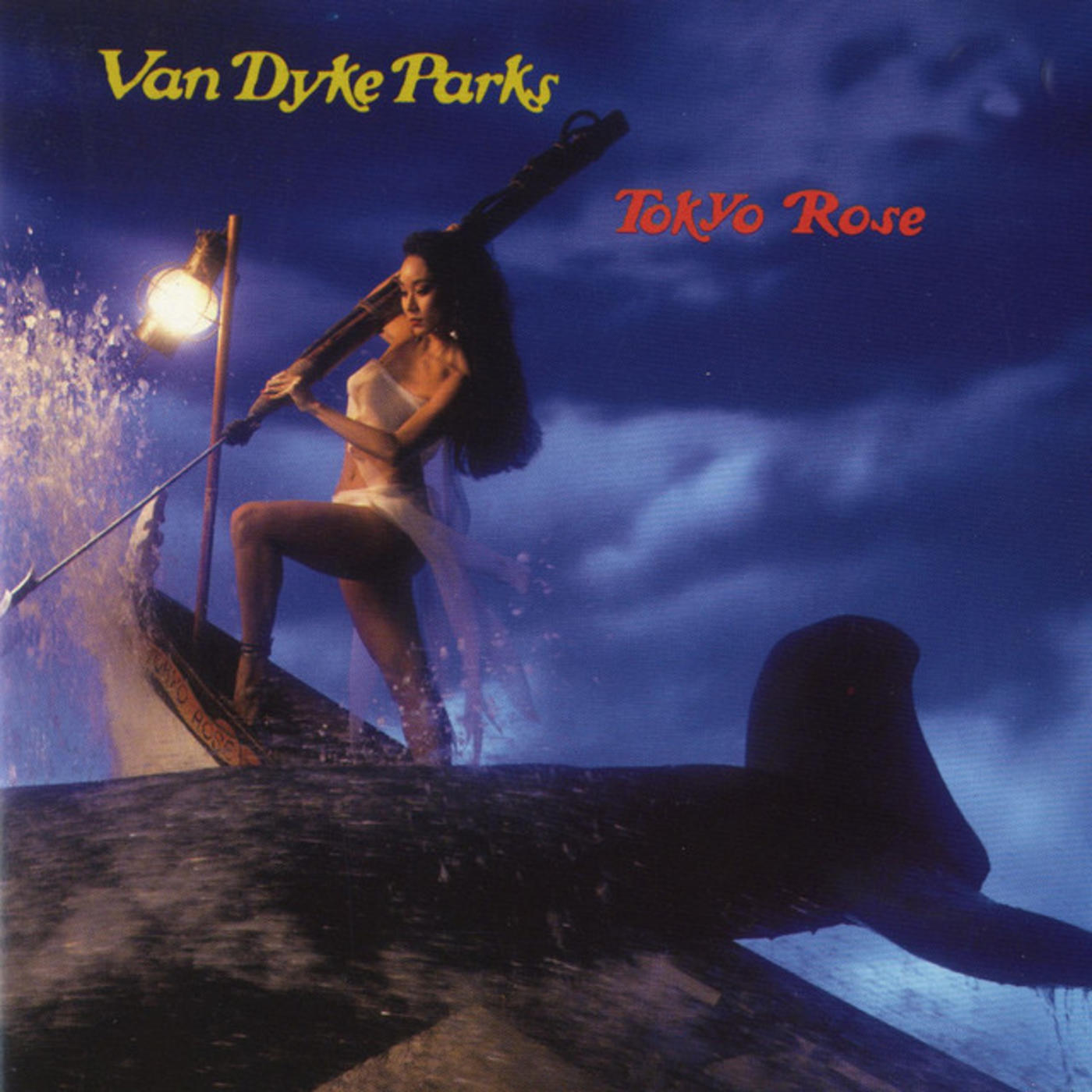

Van Dyke Parks is a true conversationalist. He speaks in fluid lines, quickly but with great care devoted to each word. At the moment, the producer, songwriter, and arranger -- who’s worked for Disney, crafted teenage symphonies to God with Brian Wilson, and arranged strings for everyone from Joanna Newsom to Skrillex – is elucidating his feelings about his friend, collaborator and fellow member of the “counter-counter culture,” Harry Nilsson.

“We typified the anarchy, the real anarchy, of the ‘60s,” Parks laughs.

“Anarchy” is an apt a term as there is to describe Harry Nilsson’s career at RCA Records. His recorded works for the label are by turns inspiring, baffling and demented. Nilsson’s 14 studio albums and three discs worth of outtakes, demos, and alternate takes are collected in the sprawling boxset, Nilsson: The RCA Albums Collection. Nilsson’s relationship with the label began with 1967’s Pandemonium Shadow Show and ended with 1977’s KNNILLSSONN, and he spent the time between those points interpreting songs, writing them himself and generally running amok, following his muse where it took him, be it to the depths of the Great American Song Book to cast-off, seemingly improvised numbers like “I Want You to Sit on My Face.”

The set makes for a long, satisfying listen, offering a chance to grasp at the through line that connects Nilsson’s acclaimed classics, Nilsson Schmilsson and Nilsson Sings Newman, to his most thrilling diversions, the animated film soundtrack The Point and the unhinged, John Lennon-assisted Pussy Cats, the musical equivalent of one of the pair’s infamous “Lost Weekends.” His voice is showcased in both immaculate and frayed variations, and his biggest hits, the Fred Neil-penned “Everybody’s Talking” and his mournful take on Badfinger’s “Living Without You,” are placed alongside less-heralded highlights like tropical noir of “Kojack Columbo” from 1975’s Duit On Mon Dei (originally titled God’s Greatest Hits, a title RCA predictably balked at) and the funky grit of “Daylight Has Caught Me,” written with Dr. John and featured on 1976’s … That’s the Way It Is.

Parks describes the collection as a set of “failures and successes.” He observed Nilsson’s career throughout the ‘60s and ‘70s, working for competitor Warner Bros (he speculates Nilsson would rather have recorded for Warner Bros. as well). The two would eventually work together, scoring Robert Altman’s largely dismissed 1980 adaptation of Popeye, recorded a few years after Nilsson was dismissed by RCA. Parks and Nilsson share a tangible connection, along with artists like Randy Newman and Little Feat’s Lowell George, as musicians as captivated (or much more captivated) by the sounds of classical music, big band and crooners as they were the sounds of rock ‘n’ roll and race records.

“He was doing something that existed before Elvis shook his hips. There was a musical continuum that Harry was a part of,” Parks explains. “…he chose music. He chose to celebrate what was in his DNA, from his mother, who was a fine hipster; who was fine fare.”

Nilsson’s RCA catalog finds him unafraid to try anything. The selection of demos presented on the set offer a look into his mindset. The discs move from the acrobatic vocal pop of “Walk Right Back” and the boogie of “Jump Into the Fire” into bare bones renderings of John Lennon’s “Isolation” and Pete Ham’s “Without You.” With nothing to obscure it, his voice is staggeringly remarkable. Even with his vocal cords in a ruinous state (see Pussy Cats) there’s fearlessness nature to Nilsson’s voice that speaks to his creative thrust.

“Harry continued to experiment [with] each record,” Parks says. “This is what was magical about the age of vinyl, when people had enough time to listen to an album and let it take them away like a good beach read. A short story, the ultimate short story. Harry would do that with albums, and he was so great at it and sometimes that is what put his relationship with RCA’s promotion men at peril.”

Indeed, RCA wasn’t quite sure what to do with Nilsson, an artist blessed with a tremendous voice and overwhelming creativity, but no desire to perform live. But they were certain what they had with him.

“He was what was hip about that place,” Parks laughs.

Though eventually Nilsson was dragged onto Hugh Heffner’s Playboy After Dark, Nilsson had no desire to take to the stage.

“They wanted him to be performing. It was ridiculous,” Parks says. “Everybody else tried it. Randy did it, went in kicking and screaming. But he went into it. So did Ry Cooder. A lot of people reluctantly went into the arena of public performance. But Harry, I’m just telling you, there’s no explanation for it except he was just too shy to do it.”

Instead, Nilsson was a man of the studio, where he could craft a singular character without having to face crowds.

“It was almost like he was creating a character that had never existed. He did that, this alter ego. I think that’s why the record was called Nilsson, not Harry Nilsson,” Parks says. “Every time I would tell him I was going over to see Jack Nicholson, he’d say ‘Tell him that’s two s-s, N-I-L-S-S-O-N.’[Laughs] He was always spelling his name out for people, branding himself. But without the public appearances to support him -- that was really the only way to rig stardom in those days. That’s what kept Harry from being a star. But you know, so many stars, let’s start with Ringo, go into a room -- but it happened to James Taylor, Paul Simon, I’m sure, [and] Bob Dylan today -- it’s living evidence. Stars will walk into a room and be miffed if someone notices them. The only thing that really pisses them off worse is if they don’t get noticed. Harry avoided that problem; [laughs] Harry didn’t need to get famous.”

Nilsson’s mythic stature is still being explored: director John Scheinfeld’s 2010 documentary, Who is Harry Nilsson (And Why Is Everybody Talkin' About Him) works well as a primer, and Alyn Shipton’s new biography, The Life of a Singer-Songwriter, dives even deeper, but the work displayed on the The RCA Albums Collection remains the most illuminating source of pure Nilsson, in all the man’s frazzled madness and sublime sentimentality. For Parks, it’s a testament to his friend, of whom he remains a great fan.

“I loved the way he would get many musicians together to play together,” Parks muses. “[It recalled] the causality of Elizabethan times, or Harlem. He’d sit all these people together and they would all work beautifully together, to really heighten the suspense, and the risk/benefit. He would step up to a mic with a bar napkin in front of him and slide some lyrics into an extemporized melody. That’s…really…big time. If that doesn’t twist your knickers, nothing will. If that doesn’t twist your knickers, you’re brain-dead. So I got to see that. Isn’t that something?”