Interview: Nick Laird-Clowes of The Dream Academy

Interview: Nick Laird-Clowes of The Dream Academy

By Will Harris

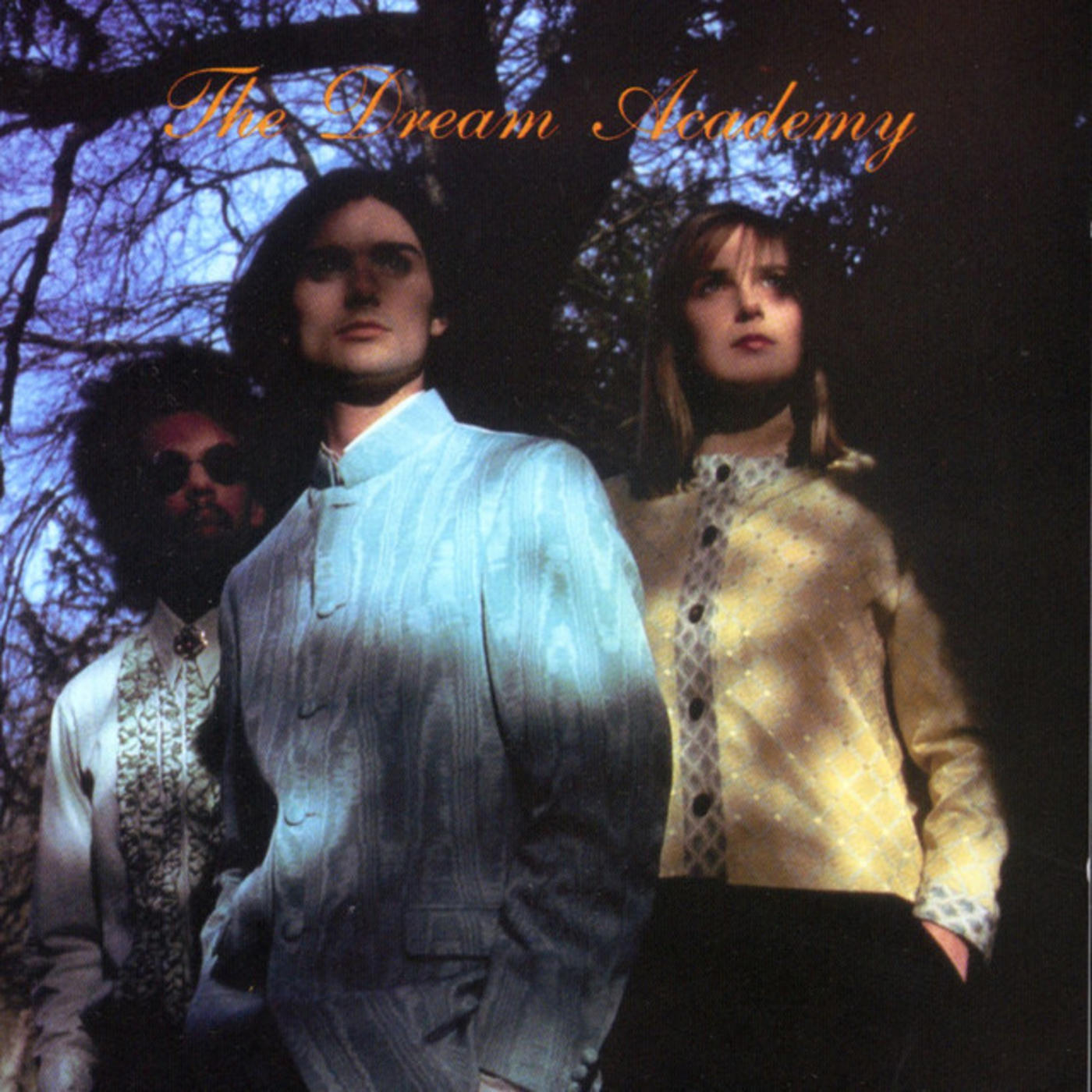

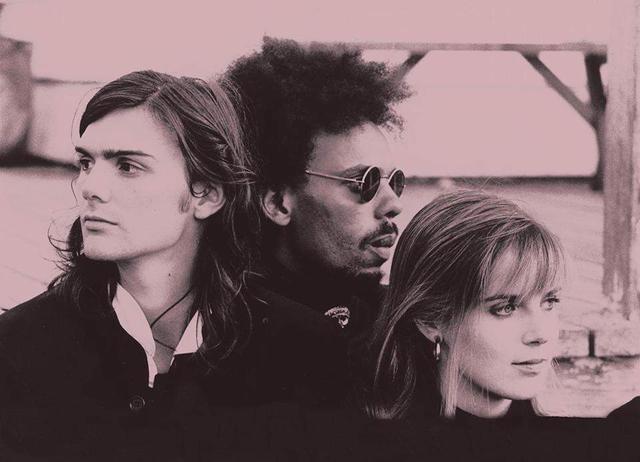

In America, The Dream Academy tends to be best known for one song: “Life in a Northern Town.” Thankfully, this is an instance where one can safely say that if you're going to be known for one song, that's a pretty great one to be known for, but it in no way comes close to telling you who the group really was, how they came about, or what sort of legacy they've left behind beyond that one song. For example, did you know they actually had two top-40 hits? True story. History tends to forget that “The Love Parade” actually hit #37. We here at Rhino, however, have not.

Last year, The Dream Academy released The Morning Lasted All Day: A Retrospective , a two-disc collection of their best work, via Real Gone Music. Earlier this year, we released the digital version of the compilation. Given that this year also happens to be the 30th anniversary of the group's self-titled debut album, we thought it would be a fine time to chat with a member of the Academy - Nick Laird-Clowe - in hopes of further introducing the world at large to the work of this highly underrated group.

During the course of the conversation, we touched not only on Laird-Clowes' time within The Dream Academy but also on nightclubbing with Marc Bolan, working with Lindsey Buckingham and Brian Wilson, his longtime connection to David Gilmour, and various and sundry other things. The conversation kicked off, however, with a look back at The Dream Academy's videography.

“This World”Nick Laird-Clowes: Well, first of all, we had shot a video for “Life in a Northern Town” in the north of England, and neither us nor the record company nor the director - who was a great director called Tim Pope - were happy with it, but it had been the video that had gone out all over England and Europe when the song was a hit there. But “Life in a Northern Town” wasn't released in America 'til a year after it was released in England. Just remember that. [Laughs.]

When we went to the States on our first major trip, we went and met at Warners, which was a highly enlightened label, like a great giant indie, with Lenny Waronker as the president and Mo Ostin as the chairman. And we'd been signed by Michael Ostin, Mo's son, and…oh, it was perfect. They were all great music lovers. And on this first trip, they said we should shoot a couple of videos, and in saying that, they put us together with a couple of young film students - or they may have been just out of film school - called Peter Kagan and Paula Greif.

They arrived at our hotel - the Mayflower, overlooking the park, where all the bands stayed - and we were doing whatever we were doing. I was still shaving! [Laughs.] But they walked in, and they had these super-8 cameras, and they let us play around with them, and…it was exactly right for our sensibilities of how we were as a band, because we thought, “A-ha! After this first attempt and getting it not quite right, we can now have input into it, and we can make it artistically the way we want it.” Because we were very involved, we loved cinema, and we wanted our thing to look like great pieces of film that matched our song, not some kind of horrible commercial or ad.

So they came in, and we shot two videos in a weekend, or in three or four days. We shot one at an abandoned CBGBs for the song “This World,” which was never a single, and that was in black and white, it was hard hitting, and it was just what we wanted: a sort of Velvet Underground meets the pastoral Dream Academy vibe. Even though it was orchestral, it was about the heroin problem that I'd been reading about in Liverpool and that I'd seen amongst my friends and other people. It was this extraordinary thing where drugs had gone from being fun to being this thing that was suddenly affecting a lot of musician friends when we were in our early twenties. What was weird was this irony: it was a full-time job to have an addiction, because you had to find the money, which meant doing something to get the money, and then find the gear. So that was our track about that, “This World,” and they were sensitive to it, Peter and Paula, saying, “Let's do it in black and white, and let's shoot it at CBGBs.” It was dark and derelict, and it was pretty amazing.

By the way, they put “This World” to radio as the first single, but it wasn't released as a single. And then radio said, “Well, it's fine, but what we really like is this song 'Life in a Northern Town.'” And I think that was some canny way of letting radio pick the single. So “This World” did have a reason to have a video, because then they could go to MTV with it, which was still relatively new at the time. Jeff Ayeroff, who was in charge of all the videos and talked me into putting part of the touring budget -or all of it, I imagine - into videos, he had said, “I think I can break the band through video, because I've just done it with this new signing called Madonna.” So there was a big group discussion, and a discussion with all the people at Warners, about whether it was the right thing to do to put this budget into this unknown new marketing tool. But it was more than a marketing tool,

“The Love Parade” NLC: After we did “This World,” we went out to the country for “The Love Parade.” We went to Long Island, and we had a blissful weekend where we all lived together and worked together, and it was an incredibly enjoyable time. We couldn't believe the joy. “Life in a Northern Town”NLC: And after that, because everybody was really happy with these, Warner Brothers said, “Okay, come on, guys, you've got the game, now let's shoot another promo for 'Life in a Northern Town.'” But Peter Kagan and Paula Grief were suddenly getting a lot of work, so they couldn't do the “Northern Town” video. Okay, now, you're really going to need to stick with me here. [Laughs.]

In England, about two years before “Life in a Northern Town” was recorded and released, Gabriel and I had the band - Kate hadn't yet joined - and we had absolutely no money, we were getting no gigs, and he said he was going to have to get a job, and he was going to take a summer job working with a fiesta group and touring England. I said, “God, so what the hell am I going to do? I'm going to have to find a job!” So I looked in the music papers that week, and there was an ad that said, “Looking for young people to host their own music program. Apply here, and send a photograph.” So I did all that, and I turned up at a church hall with two thousand other…New Romantics, they were, in those days. People with feathered hair, wonderful, like cockatoos. It was just wild. [Laughs.] And there were some punks. Anyway, we're in this church hall, and soon they whittled it down to a few hundred for the afternoon, and then we all went away. And a month later I got a call, and they said, “Will you come down and pitch to camera now?” I was in what turned out to be the last 15.

And I got the gig, and once a month I was a presenter on this youth television program called The Tube, along with a guy called Jools Holland, from Squeeze, and Paula Yates, Bob Geldof's wife. So I did that, and I wasn't good at it at all, and my heart wasn't in it, but I loved music, so it was fascinating to see U2 at their height, and Dexy's Midnight Runners, and the Jam, and then the Style Council…all these sorts of things. But you had to go to the north of England for it, and somehow it was very depressing, the whole thing, and when I went there, I just saw how the unemployment had hit England in this incredible way that it had not hit London, with queues of people outside the pubs in the day, waiting for them to open. Nobody was at work. People we interviewed were poor. And the shipyard, the great bastion of the northeast, was standing empty. Nobody wanted their ships built there anymore. So on the back of this gloom, I wrote “Life in a Northern Town.” I'd come up with the music with Gilbert, and then I wrote the lyrics about this.

Well, when The Tube heard about this - they didn't pick up my contract, so this was a year later when they heard the song - they rang me at David Gilmour's place, where I was in the middle of mixing tracks for the album with David, and they said, “Hey, we love the song, and we want to make a great video for it! We want to put it on the show!” I said, “Fantastic!” So this great, great guy named Geoff Wonfor, who went on to work on the Beatles Anthology series, he had a big part in “Life in a Northern Town,” because he showed me around the shipyard and showed me all these things and made me realize how things were…and then he shot the damned video! [Laughs.] He shot this thing with the band all in a hall in London, and shot it really beautifully. And then Warners saw it and said, “Hey, let's use this as the basis for it, and then let's use Larry Williamson and Leslie Lipman to come over and shoot the other stuff around it.”

So they came over to London, and they said, “Well, you've got the footage of the band in the hall, and it's beautifully shot and it's got the vibe, but…what's the song really about? What were you thinking of? Was it Liverpool?” I said, “No, it was Newcastle, and it was these things that I saw.” And they went with a series of other filmmakers, young filmmakers that they'd picked up in London, and everybody went out and shot on Super-8 these actual things, the real things that the song was about. And then Larry said, “I've even got footage of the Beatles that I shot, and actual footage of Kennedy, who I saw when he came through our little town in the middle of the snow in '63!” Or maybe it was '62, but either way, that was just unbelievable! So they put it together, and we said, “Fantastic! Now we've got three videos that we love!” So that's the long answer to one question, but you got three videos out of it. [Laughs.]

“Please Please Please Let Me Get What I Want”NLC: When we first got signed in England, we went to every major and every minor label, and we got turned down by absolutely everyone again and again. [Laughs.] And then Geoff Travis of Rough Trade called us back in, and he said, “I'm going to go to America, and I'm going to play your stuff to Warner Brothers and Columbia, and we'll see what they come up with. I just don't think I can do this myself.” And he had played us “Hand in Glove,” and he said, “This is the new band I've signed,” and we said, “Wow, amazing, the guitar!” Because when I first heard the Smiths, it was like the Byrds on guitar, and that was the first time I'd heard that thing for a long time. It was sort of pre-R.E.M. and things. We'd been trying to get a deal for over a year by that point, but when he came back from America, he said, “Yes! They both want it! Now let's work out who we go with.” And then when we went into his office, he said, “Oh, listen, this is the new thing by the Smiths,” and I think he played “This Charming Man” and “Back to the Old House.” And we were obsessed. We suddenly said, “Hold on, this guy may sound miserable, but this music is unbelievable!” And when we did our band rehearsals in Kate's little flat, we listened to the Smiths a great deal.

So when we had our hit with “Northern Town,” we thought we would love to show to friends, like David Gilmour and all these people, that this band has got really great songs. You might not like the way they've been done or something about it may turn you off - because some people were quite turned off by them and called them “miserablists” - but we said, “You're crazy, you've got to listen to these songs.” And on the B-side of one of their singles, because they had so many extra brilliant tracks, they had “Please Please Please Let Me Get What I Want.” And nobody had done a cover of the Smiths, so we said, “Let's do it as a follow-up to 'Love Parade.'” And we went into the studio, played it to David, and he said, “Brilliant!” So instead of going in with our usual engineer and things, he said, “Just come down to the studio on Saturday,” and it was just him, Kate, Gilbert, and me. And David programmed the drum machine and played the bass, and we all did our thing, and it was done in a day, and it was one of those very enjoyable, pressure-free things.

Because of the “Northern Town” video, Warners wanted to do a video, and I think Paula and Peter were now doing some huge ads for the first time, so they were going off into the stratosphere, so they said, “Let's use Larry and Leslie again,” which we did. And we used a deconsecrated church, which was actually The Limelight, if you remember the nightclubs of that period, which were always in churches. I think we shot it the night after Nile Rodgers had had his 40th birthday party there, because somehow we were invited to that, as was the way in those days. It was all one big, nice, happy family. [Laughs.]

And it was so thrilling that John Hughes used us… Well, he used us twice in his things, which was amazing for us, but what was particularly wonderful was that he used “Please Please Please” for what I would call the acid sequence in Ferris Buller's Day Off. [Laughs.] You remember how in films there'd always be the psychedelic sequence where everybody looked at flowers for awhile and everything went super-colorful? Well, it was definitely the equivalent for a teen movie when they bugger off school and go to look at the (Georges-Pierre) Seurat exhibition, and you get lots of close-up on the pixilation, and it was wonderful, we thought, to use the Smiths' music but our music. Because that's where we felt our place was. And then he used “The Edge of Forever” as well, which was fantastic in the love scene at the end, with the kiss and all of that. So that started our relationship with John Hughes, which was very good.

“Indian Summer”NLC: Our second album was, as is the usual thing, took a lot of time and had an all-change in terms of personnel. Hugh Padgham, who was just the biggest producer of the time, when introduced to Kate, he wanted to work with us, which… I remember sitting with Hugh Cornwall from the Stranglers, and when he asked, “Who's going to produce the new album?” I said, “Padgham,” and he said, “He'll never do it. You'll never get him. You're crazy, you're pitching way too high.” So it was, like, “Jesus, I'm not even pitching. He's asked us!” [Laughs.] I wanted David to do it, of course, but David was doing his first Floyd album without Roger (Waters), so that's where we were on that. And then there was also some talk of Roy Halee, from Simon and Garfunkel fame, doing it. I met with him - we'd worked with him on a film for Diane Keaton and sat with him - but that's when Warners said, “Look, we really want you to work with Padgham.” So we did. And we worked with different people from Peter Gabriel's band, and they fleshed us out, because we didn't have drums or bass in our lineup.

So we'd made this record, and then I'd gone to L.A. and mixed it on my own with various people, and that had been months and months and months. And then we all met up and decided that “Indian Summer” was the first single, which Lindsey Buckingham had been working on. We'd been working with him for a couple of weeks on a couple of things, and he'd just split up from Fleetwood Mac for the first time, so it was quite an intense time in his house at the very top of the canyon. It was very interesting times, to put it mildly. But we'd made that in these wonderful studios, and we had all these great people, because he'd brought, like, J.D. Souther down and the Williams Brothers and all these people to sing backup on the big chant chorus. So they said, “Why don't you go shoot it?” And somebody came up with the idea of Hyannis Port, and I knew about it from the Kennedy compound and stuff, so we went up there. Kate was with me in L.A., and Gilbert was in London, and we all met up together there, and we had this wonderful three days, with the crew really working, getting something that was more of a storyline than the other videos. But I guess the song was, too, so there you go.

“The Lesson of Love”NLC: Towards the end of the year, suddenly the record company said, “Listen, we should do 'Lesson of Love.' We should have a go at it.” We worked on it with Pat Leonard. They loved Pat Leonard. I'd written it when I was in L.A. It was written with Gilbert. It was one of these where I just went 'round to his place to do something, and we wrote it just the minute I arrived. So Warners were very keen to do it, so a friend of mine called Adam Brooks, who was a film director, he had always been a friend, and he was in London when I got the call. He lived in New York, but he was here, and his family were New York, and it was just before Christmas. And when I said, “Who are we gonna use?” he said, “I'll stay here, I'll fly the wife and children over.” And his friends who he was staying with, they said, “Yep, you can stay for Christmas with us.” And suddenly it was all done. He shot it all around where we lived in West London. And for the band, Guy Pratt and the drummer were both working with David in Floyd at the time, and Guy had always worked with us. And I think Sam Brown is on backing vocals, and June Lawrence as well. That was a lot of fun, too. And I'm still friends with Adam Brooks, but the assistant director on it was Laura Bickford, who went on to produce Traffic and was Steven Soderbergh's girlfriend for years. Whenever I see her, she says, “This guy gave me my first break in movies!”

“Love”NLC: I don't know why they haven't posted it, but the major video we did for A Different Kind of Weather is the cover of John Lennon's “Love.” I wonder if it's because they don't have the publishing. That can't be, can it? I've mentioned it to them already, but if you mention it, I'll mention to them again. [Laughs.] What was extraordinary about that was that Warners said, “Let us show you who we think you'd get on with,” and I looked at lots of different film people, and there was this new Indian director, a guy named Tarsem. He hadn't done anything yet. I mean, he'd done some things at film school, and they were great, but… I sat in the car with him, and I played him “Love,” and he said [In an Indian accent.] “I've got to do this. I have got to do this! This is amazing! And I know what to do: I want to go to India for it!” And I thought, “India? My God!”

But the record company was thrilled that Tarsem wanted to do it, because he was this wunderkind. So we looked at all these different places in India, and we ended up shooting in Rishikesh, which for me was incredible, because that's where the Beatles had studied meditation, which had brought so much to life during that whole period and that whole thing. It just seemed so right. And we went with Poly Styrene from X-Ray Spex, who was now a Hari Krishna person that Gilbert had met, and she had sung this amazing chant on the end of “Love.” What had happened was David had co-produced this album as well, and it had taken a long time because we'd had to wait for him to come off the Pink Floyd tour to finish the album, and we had so many different tracks. But when it was all over, suddenly Gilbert said, “Look, I've been working on this thing with Poly Styrene, and it's amazing.” And I heard it, and I said, “My God, I know that to do with it!” So we got to work on its ourselves, and we did it very, very quickly, and suddenly it was the first single for the album.

Anyway, we went and did this thing with Tarsem, and the very next video he did - an almost identical thing - was R.E.M.'s “Losing My Religion.” Only he didn't go to India. He shot it in a studio, and it looked fantastic, with all these strange kind of movements that he liked people to do, which we all said, “Oh, God, I don't have to close my eyes and lean over backwards, do I? “ And he said, “It's going to look amazing!” So you had to do it. And it's an amazing video. I saw it the other day, and…well, I mean, it got us to India, and that was pretty incredible. I've been back a few times, but that first time was something very special.

“Twelve-eight Angel” a.k.a. “Angel of Mercy” NLC: I'd co-written a song called “Twelve-eight Angel” with David, and they said, “We've got to do that.” So I think it was directed by…someone Greenhouse? Anyway, great guy. We went and shot it on the sands on Dungeness and weird places, remote places somewhere on the British coastline, and also in a studio. That was the final video…and that was that! The Life and Times of Nick Laird-Clowes Thus Far…Rhino: Until researching for this conversation, I'd always wondered how the David Gilmour connection came in, and I only just discovered that you and his brother Mark had been in The Act together.

NLC: Well, that's right, but his brother was in The Act because I knew David even before that! [Laughs.] My first band was called Alfalpha, and it was with two brothers, but… Well, just slightly before that, when I was 13, I ran away to the Isle of Wight Pop Festival. I ran away from home, then I pulled back, and met the police and everything. But I went to the festival to see The Doors, and there was The Doors, Jimi Hendrix, The Who… And it was six months after Woodstock, so people were doing their same sets. It was incredible! And that was the beginning for me. And the DJ there was a guy named Jeff Dexter. I stayed in touch. Every Sunday at the Roundhouse, this venue in north London, there'd be these seven hour concerts with loads of people - Boz Scaggs, Steve Miller, Sha Na Na - and I always asked for very obscure records from the guy. One time he just said, “Well, why don't you become my assistant?” I couldn't believe it.

So over the months I became his assistant, and he said, “I'm not going to be a DJ anymore because I'm going to be managing a band, and they're going to be successful.” And they were called America, and they were fucking huge! He produced “A Horse with No Name,” and he was my mentor. I DJ'ed four nights with Led Zeppelin with him on “Stairway to Heaven,” and these Hyde Park concerts with (Roger) McGuinn's Byrds… just these amazing things. And he always said, “You've got to start writing songs.” I was playing guitar, so I started writing songs, and I started showing them to him, and by the time I got to be, like, 16, he'd say, “This one's good. No, this one isn't good.” By the time I was 17, he said, “I've met these two amazing brothers. You should meet them. I think you could form a band.” So I met them and formed a band, and we got signed.

By then, Jeff was co-managing Marc Bolan and T. Rex, so we sang on the T. Rex record (Dandy in the Underworld), and that was great. And our band was on EMI, and Bolan was really backing us. He was looking after us. And Bowie, him, and the Floyd were all in one office on Bond Street in England, so I saw a lot of the Floyd. I didn't see them as in knowing them, I just saw them, like, “My God, that's David Gilmour coming into the office! Crikey!” [Laughs.] But Bolan I knew, so that was lovely. We went on his TV show and things like that.

Anyway, when he died, his patronage died, too, and therefore EMI dropped us almost immediately. So six months later, I felt that my career had started and was now over, and I was just so depressed. And then Jeff, who'd been managing us and mentoring me, said, “Come to Greece on holiday and get over it, I'll lend you the money.” And, of course, that was where the Floyd went. David went, so Rick (Wright) also went, and they all had houses there. And over the summer, I got to know him a bit. Not much. He was very shy, and I was kind of in awe, anyway.

But then we did talk at the end of that summer, and when we got back to England, my girlfriend was friends with his wife, and on the way to see The Clash, we popped 'round to see him, and he went, “Oh, what are you seeing them for? They're dreadful!” It was 1978, so I said, “No, you're mad, they're brilliant!” [Laughs.] And he said, “What are you doing?” I said, “I'm going to form a new band.” He said, “Well, if you need a guitarist, you should use my brother. Try him, he's great!” And I didn't, but then after three months I only had a drummer, and I said, “Okay, I'll try him.” And he was great.

So suddenly we were always seeing David because his brother lived with David's parents still, and then we became better and better friends. And then we made a ridiculous record called Holly and the Ivy's, a Christmas record, all Christmas carols strung together, and he and I just did it on our own. And the night before we went in to record the choir, he said, “Oh, you can have the B-side if you write a song tonight.” So I stayed up and wrote this Christmas carol, and then we did orchestra and choir on it because we were putting them on the other side, and it was, like, “Fucking hell, this is amazing!”

Then we got more and more friendly, I worked on his first solo album, and then the band split up with his brother. And I played him the demos of what I was doing with the beginnings of The Dream Academy, and he said, “This is the best thing you've ever done. If you want some help, I'll help you with the demos.” So we went down, and we actually worked with his brother as the engineer. He just came in and sort of tucked his head 'round the door and said, “This is how you use the drum machine on this,” and didn't do much, but when we came up to “Northern Town,” he said, “This is fantastic! I would definitely like to work on it.” So we worked on it together, then when we went in to make the album, the record said, “Well, who did that?” And we'd already done a demo without him that was pretty much like it, but of course, because he's David, when he put his focus on it, it really made a huge difference. And we loved working with him, because he understood. A lot of other people we worked with, we always fell out with them, but David knew you had to follow your muse and your own ideas, and he just gave me the freedom to follow up my own ideas. So the record company, after starting with other people, luckily said, “Oh, you've got to go with him.” So we did.

Before we move on to talk about how you, Gabriel, and Kate first came together, I need to go back and pick up one quick thread from a moment ago.Sure!

What was it like just being around Marc Bolan?

Amazing. I mean, I had loved the Tyrannosaurus Rex records and then the T. Rex records, so I well and truly knew all about him and the Bowie connection - “The Prettiest Star,” you know, he played the guitar on that - and all these things. I knew it and I was really into it. And he was a star. I mean, in inverted commas and big letters. He was into stardom. Not like the Floyd, who didn't want their pictures on the cover, or the punk thing that was dusting up. He had a white Rolls Royce and a chauffeur. And he said to me, “Why don't you come out nightclubbing?” And I just didn't know if I could sit in the car with him. But he said, “We'll go in the white Roller, and I'm going to call you 'darling' all night, but I'm not gay.” Actually, I think he said, “I'm not queer!” [Laughs.] But he said, “I will be calling you darling all night,” and I said, “Okay,” and we went to these clubs, and he'd say, “What do you want to do with your career, darling?” And I said, “I want to be a film director,” or something. Anyway, it was incredible.

I don't know why - I guess it was just because he was a good guy and he somehow liked us - but he suggested that we work on his album and sing backing vocals. And we'd never done a session, and we were harmony singers, but he didn't want harmony. He took us into a tiny room in Air Studios, and I remember that at the same time George Martin was in there mixing The Beatles' Live at the Hollywood Bowl, and we'd stand outside and hear, “Oh, no, I don't think we should do it like that,” all the talking that they cut out. Anyway, I digress! We were in the studios, and Bolan was into slowing the tapes down and having me sing… He'd worked out the ratio of notes to, if you sang at half speed, what the notes would be, and then he'd double-speed it and stick them all together. I mean, we weren't even in tune, and we'd say, “That's terrible!” And he'd say, “No, hey, it's about the energy. It's about the energy, not whether or not you're in tune.”

He took us to the Roxy club one night, took us all there and just said, “You've got to come and see this, there's a new revolution breaking.” And we went, and the first thing I heard when we got into this tiny, dark club, everyone looking totally different than us, was “Anarchy in the U.K.” And I thought, “My God, this sounds like 'My Generation' by The Who!” And everybody was pogoing and spitting, and Billy Idol and Johnny Rotten were having a kicking fight, and everyone was wearing ties. But they didn't sort of go, “You're a hippie!” They loved Marc. Everyone came up and talked to him. And he went on tour with The Damned! So that night, we went back, and we all said, “Right, that's it: three-part harmony, America and Crosby Stills & Nash style music, this is wrong. I'm gonna cut my hair, get a tie, and start playing electric!” And that's also why the band split up: because we were suddenly in the wrong place at the wrong time. We'd seen the change. Marc was on the money, and he was right there. He was a really fascinating guy. But then he got a TV show, which was in '77, and he died shortly after that. He was quite gloomy at the end, I have to say. Well, at the end, he was rather up again, but somewhere in that middle period after we met him, he'd been so huge and now the records weren't as huge, and…it just wasn't quite the same.

When you set aside the three-part harmonies, what led you to the sounds of The Act and then to the more pastoral material favored by The Dream Academy?

Well, we went from the three-part harmony acoustic stuff to The Act, which was kind of new wave. Elvis Costello meets the Byrds meets Tom Petty, really, is what I was trying to do. I'd gone to New York, I'd gone to the mod club, I'd seen what was happening. And I'd stayed there for a few months, and I just thought, “Right, this is it: I've got to form this kind of band.” And we got signed, amazingly, by Joe Boyd to his Hannibal Records. And Joe was my hero, because I loved Nick Drake! But we weren't doing anything like Nick Drake, and we were working with John Wood, who was Nick Drake's engineer/producer, as well as Joe! So we did that, but it didn't work.

And this was the second band I'd had. A lot of people never got any records out, and I'd made three records, and one of them never got released, but I made one with the first band, one with the second band, and they'd had a really good shot. So I had to think, “Why isn't it working?” And that's when I realized - to my horror - “I'm copying other people! I've been copying people because that's how I've learned to do it, but by copying, I'm always a stage behind. By the time I get my Byrds / Elvis Costello thing out, Elvis is on to a whole new thing.”

In fact, the salutary lesson was actually meeting Elvis somewhere, and him saying, “What band are you in?” And we said, “The Act.” And he went, “Oh, are you the one that does the Byrds or the one that does me?” And by “the one that does the Byrds,” he meant R.E.M., and we were the one that did him. And I was horrified! I had to say [Muttering.] “I think the one that does you.” But I was thinking, “Oh, God, that's a terrible thing to say!” So what was great was realizing - after months of torturous soul searching - that you can't copy, you've got to find your own voice, however hard that is.

I had met Gilbert Gabriel, he'd been in the last incarnation of The Act after the album and had come with us on tour. And on tour, he played me Erik Satie and things like that, and he said, “I think you're too focused on the Beatles.” And this isn't something he said later. He said it at this point: “You're too focused on Beatles-type things. There's another world. Listen to all of this amazing music!” And he played me Ravel and things, different types of music. So he and I started working together, and for the first time I started co-writing songs. He had bits of music, and we were really into an arty, experimental vibe where we'd try anything. And the rest of the band in The Act were horrified. They said, “You don't need him! For fuck's sake, man, the songs are great!” But I liked what was happening with him, and that we were thinking in a different way. So we just didn't do anything for a year. We just tried to find our own voice. And along the way we met Kate St. John.

Funnily enough, the whole of London was doing white-boy funk, everything was post-New Romantic, and there was a real preponderance of white dance music happening, and…we liked it, we just didn't really do it. We found that we had this...thing. And I suddenly thought, “Nobody is playing acoustic guitar.” You could pick up a good acoustic guitar for nothing. So I thought, “Well, I'm going back to acoustic guitar.” And these orchestral instruments… The synths could be played to sound like strings, and then add Kate to that with her wonderful real oboe sound, and add my acoustic guitar to that, and then use drum machines for drums, and then we started adding tympani and all these other things. And at first I said, “My God, this sounds like Phil Spector!” But then I went, “No, this sounds like Pet Sounds!” And nobody else was doing it at that point.

It was an easy thing for us to just add the classical instrument sound. People had used classical instruments to make their psychedelic masterpieces, but we could do it because technology allowed it, and when we came out with our album, not only did we have this new sound which wasn't what was going on at all, but we also had not bothered to have our hair cut in the way that everyone had at time. [Laughs.] They all had this kind of rockabilly hair cut, even if they were doing the white boy funk. So we went with our kind of more hippie-ish look, which was almost a punk stance, because hippies were ever so out. And we didn't oAverdo it. It was just how we naturally were. And at first everyone was really negative about us, but then we started playing these nightclubs after bands who were playing funk and other bands who were around at the time. People like Mick Jones and the Bunnymen would come see us, and we suddenly realized, “Hey, we're doing it our own way!” And that was the biggest lesson for me: if you can find your own voice, it's the only way, really.

So how surprised were you when “Life in a Northern Town” actually took off as a hit?

Oh, you've no idea. [Laughs.] Look how long I'd been going at it - ten years! - and then the three of us had this thing together…and it was just the three of us: no bass, no drums, just us top-lining the thing and writing the songs. We made a really interesting song in a room. If we played any song by any band, including ourselves, we sounded like…us! It was very strange. I'd never had that before. So we'd got signed, which was amazing, but when you've had two bands and you've had no hits even though you've been on television and known people, you know how hard - almost impossible - it is.

Well, we were having our photographs taken, and we always thought to watch Top of the Pops every Thursday night, and we'd all been watching it since 1964, probably, so we said to the photographer, “We have to stop and watch Top of the Pops.” So we sat down and watched it, and as we were watching it, they always did this, “And in the charts…” They'd do the rundown. And they said, “At #14, The Dream Academy's 'Life in a Northern Town.'” Nobody had even told us! You'd think if you… If it had stopped there, I would've always been able to say, “I've had a top-40 hit!” But the record company didn't say a word…and they even had a picture of us! We could not believe it. After that, though, because we were signed to America, the English record company weren't doing anything, and they said, “We're not going to put any money into this. We're not going to put any adverts up.” I suppose it didn't fall into their business model. It wasn't good for them one way or the other, whether it was a hit or a miss. It was, like, “It'll be a hit or not. It's just a freak record.” But it just went on climbing. And a couple of weeks later, it was at #15, and #9 on the Irish charts, and…that was it! It happened so quick, and without any paid ads. It was just a fucking phenomenon.

In regards to the band's debut, your story about that encounter with Elvis Costello ended up being extra funny, given that The Dream Academy actually ended up having a member of the band that was “doing the Byrds” - Peter Buck - contribute guitar to that first album.

Right! And that was because of Joe Boyd. Everything fits in. Suddenly we were always going to parties, and it was, like, “A party? Yeah, I'll be there! Can I bring the band?” “Of course!” [Laughs.] And there, on a lovely summer evening, was Joe, who now felt vindicated, because he'd heard “Life on a Northern Town” when it was a demo and said, “That's great! I think that's a hit!” So even though he'd put a lot of time and effort into The Act that hadn't worked, he felt vindicated. And there he was, so I said, “What are you doing, Joe?” He said, “Oh, I'm doing the new R.E.M. album.” “What?” “Yeah, yeah, Peter and Michael are coming to the party.” And all of sudden, there was Peter Buck. I said, “My God, I love your stuff! We're making an album with David Gilmour. You wouldn't want to come down, would you?” He said, “I'd love to! I could play electric 12-string on one of the songs.”

We had one more song to do, so he came down to David's place at Hookend, which used to be Albert Lee's studio, and he sits in this huge barn, poor Peter, and David had him right in the middle of a vast, empty room with Voxes, Dave's old things, using a vintage early Rickenbacker, not Peter's. And he sat there, and he dripped sweat. He was absolutely nervous as hell! And he kept coming up, dripping with sweat, going, “I'm so sorry, I'm not quite in time. I'm so sorry!” But anyway, we worked and we worked, and we finally got it. But that's why he was there: because Joe, of course, had also produced the first Floyd thing (The Piper at the Gates of Dawn). We were all, marvelously, connected. And Peter was wonderful. I loved it.

There's one track on The Dream Academy that isn't produced by David Gilmour, and that's “The Love Parade,” which was produced by Alan Tarney. Did that come about because of Warner Brothers, since they'd had such strong returns with his work on a-ha's “Take on Me,” or was that coincidental?

No, I think we did it before “Take on Me.” I'm pretty sure we did. What happened was, we had a pretty good demo for “Love Parade,” and we loved it, and when we made the record with David, somehow we never got 'round to it, and he always said, “Well, the demo's pretty good, and it's not really my kind of thing, and it's good what you've got.” And I said, “Well, okay.” But at the end of the album, when we listened to it, it wasn't good enough. But we still all adored the version, so Geoff Travis from Rough Trade, being a really canny music-loving thinker, said, “What about Tarney? He did 'We Don't Talk Anymore,' by Cliff Richard.” And we all loved that record.

There was a touch of irony about it, because we knew this was coming from right field instead of left field, and we thought, “Well, that's a really inspired idea, because nobody would think of us working with Tarney.” Because we felt that our peer group were the people we were working with, like Peter Buck or Joe or David. So it was really interesting, and we said, “Well, let's see what he thinks.” And he said, “No, I'd love to do it!” So we went to his house, and we worked with him when the album was finished, and we made that on our own just before “Please Please Please.” And Tarney didn't co-produce. It wasn't like I could say, “I want this, I want that.” I did a lot of that, and he walked out a couple of times because of that. And it was right back to that old thing which had happened every time when I'd worked with anyone before David. It was just silly things like, “Can I just get on the faders and push the keyboards like this and put more echo on the voice?” But it was always happening to me. [Laughs.]

So it was brilliant, and… Well, no, it wasn't brilliant, but he did it, and then we mixed it again, and it was great. But he taught us a lot. I mean, he didn't triple-track vocals. He tracked them up about 12 or 15 times! He had real special techniques, and he also had quite strong ideas. On the best-of retrospective, we'd been recording songs for B-sides, and one of them was called “The Last Day of the War.” I put that on when he asked what we'd been doing, and we played him that after “The Love Parade,” because we didn't think it was going to be a B-side. We were pretty pleased with how conceptual it was. But he listened to it, and he said, “Why would anybody want to write a song about the last day of the war? My God!” And he just put his head in his hands and he just said, “Commercial suicide! Suicide!” [Laughs.] And I see why he said that. So he was wonderful, but he just came at things from a totally different place. He was pure pop, and he was very, very brilliant at it.

You know, I meant to ask this earlier when you first mentioned her, but is it true that you first met Kate at a party and just asked her to join the band?

Yeah! Gilbert and I had been working together about six months, and we were called Politics of Paradise when we played together as a duo with tapes of things that we'd recorded with David before we did our demos. In a confusing twist, we were often supporting The Act, opening for my other band, but then Gilbert would sometimes support Politics of Paradise with his band, which he called The Dream Academy, which was a very ramshackle bunch: a guy on sitar, a girl playing clarinet, and it was all without lyrics. At some point, I rang him up, and I said, “I just got this blinding flash: we'll call this band This Boy and the Dream Academy!” Lots of bands are named after famous old songs, so I thought, “Well, how about 'This Boy,' by the Beatles? I love that song.” But then we eventually dropped the “This Boy” and just became The Dream Academy. So he's got this ramshackle bunch of people, and I suddenly thought, “Well, this is what we're gonna do. We're gonna fuse these things together.”

And then I went to this architects party - the Architects Association - because a friend was DJ-ing, so he was able to have a few friends who weren't architects. And somebody said, “Oh, you're looking for people who play weird instruments, aren't you?” I said, “Well, not weird instruments, but…yeah, that's right, I am looking.” This was the guy who co-wrote “Buffalo Stance” with Neneh Cherry later, and he said, “Oh, you want to meet this girl.” So I went up to see her, and first of all, she was devastatingly beautiful. And then she played in the Ravishing Beauties, and they were a band I'd read about in the NME, and…they were cool! I mean, they'd been supporting The Teardrop Explodes and things! So I said, “Oh, yeah, I know about you. I'm working with this guy, and we want to use classical instruments. Is there any chance you could come and rehearse with us?” And she said, “Of course! When?” I said, “Well, we're working tomorrow.” She said, “I'll come up with you on the train.” And it took hours and hours, and we had some of these ramshackle guys - the sitar player and the clarinetist - and she heard all that, and then we played “Life in a Northern Town” as it was, which was still called “The Morning Lasted All Day” in that incarnation. And when we left, she said, “I know other players who are much better than those guys, and I'll introduce you to them.”

And she introduced me to Adam Peters, who went on to score Ocean Rain for Echo and the Bunnymen, and these other people she went to college with, and soon we were working with them. So that was a very happy and lucky thing, because then I started to hear what she did, and she took up piano accordion quite quickly, and I thought, “If she sings with me, that's one thing, and if she plays piano accordion, that's another amazing thing, and then she plays the oboe…” I started always figuring her into arrangements, vehicles that would work with her using the most possible.

With Remembrance Days, did you go into the album saying, “All right, we've had a big hit, now let's build on it,” or did you have the mindset, “Well, that was probably just a one-off, so let's just keep doing what we're doing”?

Well, I mean, we were pretty deep into production and set on making great, loving records, and I felt, “Now's the time.” When you've had a hit, you can do what you want. The trouble was, I didn't have my old team with David and so forth, so I had new people to get to know. But I was very heavily focused on making what I wanted to make, which was brilliant-sounding records. And Warner Brothers, luckily, because they were of that world, wanted that, too. So I got really into arranging and to making the thing sound like… I mean, that record, which is Kate's favorite record of ours, when I went back to make the retrospective, the tracks sound like they're spun out of gold. You just can't believe the amount of work we did and the amount of recording and how beautiful it sounds.

Compared the first record, which I adore, because it's where it all started, but the guitar sounds and things… On Remembrance Days, with (Hugh) Padgham, the techniques and recording, the acoustic 12-string and the drums from Jerry Marotta, Larry Fast on keyboards, and Hans Zimmer. We were holed up in Zimmer's studio for six months. He had this little place before we went to Hollywood. So I think it was…difficult to make the second album. They call it the sophomore jinx, because it was because we'd been on tour, promoting all around the world, for a year. No, more than a year. Going on two years! But we had these things, and I wanted to make them as golden as possible, and that also involved a good deal of arguing with Hugh. And in the end, when I went and played them all for Lenny, he said, “Well, just take it on your own. Come here and just mix them with people here. Get it the way you want it.” So that was amazing.

But, no, I didn't know how to think about hits. “Life on a Northern Town,” the only thing I can say about it is that it was the only track up to that point that I'd ever gotten exactly the way I'd heard it in my head and exactly the way I'd wanted it to sound…and we mixed that again and again and again. That was a double-edged sword, because I thought, “If that's the way you do it, then I'm going to do it on all these things.” I was pretty single-minded about getting it right like that, regardless of what anyone else was saying, and that brings its own reaction from people. But, hey, I think some of those things… I dunno, I just think some of them sound amazing to me. I mean, “Here,” we played the record at my mother's funeral! And “Hampstead Summer” and “Indian Summer,” they just sound amazing. I love them right down to the last second of the fade. And that's what you're meant to do. That's what record making is all about.

As far as other folks who participated in the album, Patrick Leonard always struck me as a perfect choice to work with The Dream Academy, particularly given his subsequent work as part of Toy Matinee.

Ah! And who I then went on to work with on 3rd Matinee!

Indeed. And then you had Lindsey Buckingham assisting on a cover of The Korgis' “Everybody's Got To Learn Sometime,” which is so unlikely that there would seem to have to be some sort of story behind it.

Well, we'd already done a version of it with Adam Peters - he was playing electric cello - and Hugh Padgham, and it was like the missing track off The Beatles' White Album, and it was so unlike “Everybody's Got to Learn Sometime,” but it was fantastic. But it wasn't quite finished when I went to L.A. and Lenny said, “Well, don't go back and mix with Hugh, stay here and work on your own.” So he said, “Let's send it to Lindsey.” And Mike Ostin had said, “If you'd like to, we think you should work with Lindsey.” And I was a huge fan, of course, particularly of Lindsey's work with Fleetwood Mac because of Tusk. He obviously had great music-making and record-making sensibilities. Lindsey's production can take a song and make it into a complete masterpiece. He's an absolutely amazing record maker and a really original person. So, of course, I wanted to work with him.

But when Lindsey heard it, he didn't want to work on that version. He said, “That's great, it's like (The White Album),” but then he immediately set about tearing everything out and starting again. So we worked on that for a couple of weeks, and then I played him “Indian Summer,” and he said, “Oh, I'd definitely love to help work on this.” And I think it was during that time when he came back one time, and we were, like, “Why has he been so late?” And he was even quieter than usual. And then he said, “I've just quit the band.” It was, like, “Oh, my God, no, this is catastrophic! Or not.” [Laughs.] Kind of covering ourselves. But it was great working with him. Lindsey worked pretty, uh, fueled, I'll put it that way. Let's say no more, as you can probably imagine what I'm talking about. But it was quite an experience!

When the time came to do A Different Kind of Weather, you got back together with David, who served as predominant producer.

Luckily! We started with Anthony Moore. Anthony had worked with David on the A Momentary Lapse of Reason album, writing the lyrics for David. He had asked me to work on that album, and I had said, “My God, I've got the second Dream Academy album, and I've got to put everything into this. I cannot. Everything's relying on this. And this is David's first album without Roger (Waters), and I…” Anyway, he wrote with Anthony, and Anthony was an old friend of mine. He had a band called Slap Happy, and he was - and is - a very interesting guy. He lives in the south of France. He's a professor of music, and he's a fascinating musical conceptual guy. But I met him again when he was writing lyrics for David, and somehow, when I said something to Geoff Travis, he said, “Oh, you should ask Anthony!”

So we started doing demos with him, and then every time David was coming off tour - because that tour went on for years! - he would come and listen to what we were doing, and he'd play on something, and then it just became obvious that… I think he said, “Look, you're almost there, but why don't you just take some time, write a few more songs, and in a few months, when the tour's over, I'll come, we can move to (my studio on) the boat, and we'll all work on it together.” So after we'd all been working on the record for about nine months, we suddenly started working with David again - and Anthony! - and it was brilliant. It was a wonderful full circle for the whole thing, for our third and final album. So it was pretty interesting.

So when the band finally came to its dissolution, was that by mutual agreement?

Uh, no. [Laughs.] I'd say what really happened was that it was a divorce of three people. It's always painful. It's splitting up with your girlfriend or you wife, only now it's two of them. But, you know, we'd been together for nine years, Gilbert and I had known each other for 10 years, and… [Exhales.] You know, Kate and I were involved, and then all these different things. All the Fleetwood Mac stuff. You know how it is. All these different things. But what happened is, you get this dynamic with a band at the beginning where you fall into roles, and I'd had these two bands before, and my role was to listen to what everyone said and then fashion it into what I thought was right and then take it to the record company. And nobody ever had to say anything. We all just did it in this way. And I knew it wasn't always great for everyone else, but it was working.

When we got to the end of A Different Kind of Weather and we made (our cover of John Lennon's) “Love” - Gilbert brought that to me, and then I'd taken it and worked on it on my own, and then we produced it together - we did a final tour. It was a freezing cold winter, there was snow, but we played and people came, and David came and played at the final gig. And then Gilbert suddenly said to me that he'd felt marginalized. He said, “I don't just want you making all the decisions now. I want to make them on my own.” And I said, “Wow, okay, I understand, and I don't want to argue all the time, so okay.” So now we were down to two.

And then Van Morrison, he'd loved our version of “Please Please Please,” and he said, “It's brilliant! It's back to folk music!” I mean, now it sounds like a very arranged piece, but within the context of the times, he had heard it as a return to folk music. And he had become friends with Kate enough that she invited me to dinner with him, and I had this amazing dinner with him, and…that was about two years before. But just after Gilbert left - I'd told Kate the whole thing - and she called me and said, “I've had a call from Van Morrison, and he wants me to join his band.” And it was, like, “Fuck! Oh, no!” [Laughs.] It was, like, the writing was on the wall, you know? So I called Warner Brothers, and they said, “Okay, well, that's terrible, but don't worry, we'll go on together, because it's great.” And then six months later, I'm in a different place, and then we spoke and said, “Let's just not do it like this. I'll make a solo record, and we'll go at it another way.” And that was it.

And then of course there were the dark times, out of which came the Trashmonk record. Because you've got to go deep down into the darkness before you can even… [Hesitates.] There were a lot of false starts. Funnily enough, you think, “I'm never going to make it, I'm never going to get there,” but then suddenly you're there. You're always in the process, trying to make it, trying to find a new way, but every piece of work you ever do is a new mountain to climb, and you've just got to climb that mountain, find out what you're doing wrong, and fix it. It's the same with everything. I don't find it any easier now than I did then. It's just how it is.

I got a call from Adam Brooks, the guy who made the “Lesson of Love” video, saying, “I loved the Trashmonk record, I'll be in Paris - I'm shooting with Cameron Diaz - and do you want to come over?” I said, “Yeah, I'll be there in Paris next week.” And then we stayed up all night smoking dope, and he said, “I love Radiohead,” and I said, “Yeah, I love Radiohead!” So we listened to all this stuff, and then when I got back to England, he said, “I'd like you to score the film (The Invisible Circus), and I want to put some Trashmonk songs on the album. Probably no one will let you score it, but I think you could do it.” So from there, I made the demos, they picked it up. And then Griffin Dunne, I did his movie (Fierce People), and then Nick Broomfield's war movie (Battle for Haditha), and then it went on from there. So in a way you get a slight respite from it when you do the movies, because you've got a director there saying, “No, it's not what I want,” and then you've got to change it immediately. If you haven't written a love scene right, it doesn't matter if you say, “I think it's brilliant.” It doesn't really do it. But now I'm making another record, and I don't care if there's no industry anymore. [Laughs.] This is why I went into it, and I've got all these songs, and I want to make them, so…that's where we are.

Okay, just so you know, I'm in the home stretch, because I know I've kept you for quite awhile…

No, no, this is fantastic. If I get to go over it myself, it's like therapy!

Well, I was just curious about the experience of writing with Brian Wilson on his self-titled solo album.

Ah, well, that was amazing. So I'm in L.A. with Kate, and we're at this point where Lenny has said, “Stay here and do the mixing,” Gilbert's back in London, and I'm working with Lindsey and mixing with James Guthrie, who did all the great Floyd things like The Wall and everything. And then when it was done and finished and we were going to shoot the video, I get a call from Lenny. I've now been away from home for three and a half months, I've got so much at home to do, and he says, “How are you feeling?” I said, “Oh, great. The record's done, we're just going for the weekend to shoot the video, and then I'm going home.” He said, “So you're longing to go home?” “I am longing, yes.” And he said… [Sighs.] “Look, I know you are. But if you stay, I want you to try and work with Brian Wilson.” I said, “Oh, uh… Ooooooooh…” [Laughs.] He said, “Look, come in, I'm going to play you some things, and I want to tell you some… Well, look, just come in.”

So I put down the phone, of course, and called my manager, who said, “Oh, no, you're not staying! You've got to come back!” I said, “They want me to work with Brian Wilson.” “Fucking hell!” [Laughs.] Because Brian Wilson, he might've been in a bad way at that point - nobody had seen him for a long time at that point - but…it was Brian Wilson! So I went in and listened to the stuff, Lenny played it, and he said, “What do you think?” And I said, “Well, the lyrics aren't good.” He said, “Right, we're going in tomorrow, and Dr. (Eugene) Landy's going to be there, everyone's going to be there, and you've got to say what you actually think. That's the deal.” So we went in, there's Brian, he looked very…odd. I mean, now I look back at the pictures, he looks young, but at the time, he looked very odd to me. He was in one shirt, and they put another shirt over him, and…he looked very much like the guy in a village who's the outcast.

Anyway, they put the music on, and luckily Landy wasn't there, and he said, “What do you think?” And I said, “I don't think the lyrics are right.” And immediately Andy Paley said, “Hey, those aren't his lyrics. Landy said he had to write that. He's got this one with these great lyrics about being frightened of the animals and things.” I said, “I really want to hear that!” [Laughs.] I mean, being frightened of the animals? That sounds like exactly what we want to hear from him! Anyway, Brian said, “Why don't you come in tomorrow?” And I said, “Okay,” and I went in on my own the next day, but then it was like Fort Knox. It was very, very strange. It was, like, “You're not to use a tape.” I said, “I have to use a tape if I'm working with Brian. I always tape when I'm working.” They said, “Well, you have to leave it when you leave.” I said, “Fucking… Whatever.” So I sat with him, and for about the first 40 minutes, Brian sat at an upright piano singing “Roll Out the Barrel” for a lot of the time and saying, “It's like when we were in London and we were in the back of the limousine in the '60s! Roll out the barrel…” It was just completely… [Trails off.]

Well, anyway, finally I kept kind of edging toward this one song that he had that I liked, but we were nowhere near getting to a place where we were discussing his lyrics. He really, like, out there, and I could just see he was going to be there. So finally I said, “You know that song 'Walkin' the Line'”? He said, “Yeah, 'Walkin' the Line.' Yeah, what are you saying?” I said. “I think it's got brilliant words in the chorus, but…I don't like the verse.” I mean, it sounded like “Sparky's Magic Piano.” It just wasn't good. But the song was great. So he said, “Well, how do you think it should go?” And I said, “Well, I think it should be like” [Singing.] “I walk the line / I walk the line every day for you…” And he just went, “It's genius! I'm going to tell Dr. Landy you've got to work on our whole album!” And he went out and called Dr. Landy, and I had my tape of Brian saying, 'It's genius!'” Well, I got out of the studio, and they called me when I got home and said, “You've taken the tape.” I said, “It's my cassette that tells me what I did.” They said, “No! You bring it back here!” I said, “Well, I'm leaving in the morning.” And they said, “Well, if you give it back, you might get to work with Brian on the rest of the album.” And I said, “Well, I can't.” So that's what happened.

And, you know, it's even more thrilling now. It's played a lot more now than it was then, since Brian's return. I don't know if you've seen any of his concerts - he's done Pet Sounds and Smile - but, man, it was brilliant. Just incredible. And it was brilliant and incredible to work with him. And Landy did come in that afternoon, and I don't know if you ever met him or if you've seen pictures of him, but…Brian was odd, but you'd go, “Who's the mad one here?” [Laughs.] But what a thing. What a chance to have gotten. It was wonderful.

And you mentioned how you were otherwise occupied when you had the opportunity to write with David on A Momentary Lapse of Reason, but you did end up writing on The Division Bell.

I did. And it was brilliant.

How was it to sit down and write with David in the context of a Pink Floyd song?

Well, he asked me if I would help him on his vocals. That's how it started. Because when you sing and you're like David, you sing and then you come out and you have to listen to it, and if you say to your brilliant engineer, “What's it like?” [Hesitates.] Non-singers often can't quite hear… It's not that they can't hear the tuning, but they're, like, “Yeah, it's pretty good,” and David… Well, because we'd worked together so much, he said, “Would you come and help produce my vocals?” So I said, “Sure.”

I'd been away working on the 3rd Matinee record, so I'd been in production-line work. I mean, Pat Leonard wrote a song a day! And I was the lyric writer on that, so I'd have a pencil, he'd have all the instruments, and Richard Page would sing, and that went on for months and months and months. So when I came back, David had done the production of the vocals, so he started playing me what he'd got. And I was so used to doing this process with Pat, thank God, and said, “Well, that's great, but you haven't got that, and that gets boring.” And somehow I spoke with enough authority about whatever it was that he heard it, and you always hear it when it's the way you're thinking, so he said, “Okay.” So this went on. He'd say, “Okay, come again next Wednesday, and let's have another listen.” So we had lots of red wine, and we'd listen. He'd split up from his wife of years and years and years, and he had this new girlfriend who later became his wife (Polly Samson) - they've now been married for 20 years and they've got four children - and she'd written some other lyrics on quite a few other things as well, so we'd just be sitting there listening, and then they'd say, “What do you think?”

Anyway, it went on and on and on, and one day he just called and just said, “Can you come over? We're in the middle, and we can't get this thing.” So we sat down, and…we were all quite drunk. We were definitely drinking all the time. [Laughs.] And we were playing word games, cut ups and things like that, and very much into, “Let's try all these different things.” And then I asked him… I know what it was! He had this great tune, and then he said, “I haven't got a lyric for it.” I said, “You went camping with Syd Barrett! When you were 16, you were friends, long before the Floyd. What was he like in those days? I've heard all the other things, but what was he like?” And he said, “I never thought he'd lose that light in his eyes.” I said, “That's it!” So I started writing, and then I said, ”Look, I've got this,” and he said, “Oh, I've got this,” and she said, “I've got this.” And that's when he said, “Congratulations: you've co-written your first Pink Floyd song.” Or something like that. But, anyway, that was “Poles Apart.”

When I was helping him work with his vocals, he'd said, “Well, obviously, I'm not looking for anyone to co-write anything.” And I'd said, “Of course, sure, that's fine.” But suddenly it was different. And then we worked on “Take It Back,” which I loved. He had this great idea about Gaia being a woman who could take the earth back anytime she wanted, and the three of us had been working on it. I drove back down Portabella Road near my house at about four in the morning, really the worse for wear, and I pulled over onto the side of the road and I went, “Right!” And I got the last four-line stanza. And then I went, “Fuck! Now how do I pitch it to them?” So the next day, I went in and said, “And then there was this…” [Laughs.] And they went, “That's it! Done!” And I think it was the last song written for the album. And, you know, I wrote lots of bits in between those two things, and…it was amazing.

And then I went to Nepal to study with the Buddhists, the album went to #1, and he called me and said, “You've got to come out and be on the tour! You can come wherever you want!” I said, “No way! I'm in Nepal!” But then I saw that they were playing New Orleans that weekend, and I thought, “New Orleans? Oh, my God, I could be in New Orleans?” I picked up my phone and said, “Did you mean what you said about…?” “Of course!” “So New Orleans?” “There's a room waiting for you. Be there at the weekend.” I was, like, “Oh, my God.” And, of course, I stayed on that tour for months. They had their own jet and everything, and it was completely wild. And lots of my friends were in the band and working on the crew, and it was just… I stayed so long on it, I finally thought, “I can't keep doing this.” It was the same as the thing when I was helping him with his vocals. He'd come off stage and say, “What'd you think?” And I'd say, “Well, I mean, you were playing, but I didn't even think you connected to it 'til about the second or third number.” “You're right. I was sleepwalking. I wasn't even there.” I felt like I was becoming a kind of coach, and I thought, “I've got to get back to my own work.” And I left the tour when they went to Canada, and I went to stay with my friend Adam Peters in New York. I slept on his sofa for three months and started what became the Trashmonk record. I started working just in his tiny little front room, and that became Trashmonk in the end.

Okay, and I promise this is the last thing that I plan to ask you, but solely for my own personal interest, you sing harmony vocals on one of my favorite semi-obscurities: Duffy's “Sugar High.”

No fucking way! That's amazing! That is amazing. Stephen Duffy…

I love that album. And given that I'm in the States, you can imagine - since it was released more or less in the pre-internet days - what an incredible pain it was to even obtain a copy of it in the first place.

That is just thrilling. You know, he's got a new (Lilac Time) album. I hadn't heard from him for years, and he wrote me to say… You know, he made a killing on the Robbie Williams thing, and he bought a house and got married to Robbie's keyboard player, and they live in Brighton, and they've got a kid and a dog now. And he suddenly said, “We've got to start our friendship again.” We were really good friends, because we had the same manager: this guy Tarquin Gotch, who was working with XTC and was John Hughes' music supervisor in the end. So we knew each other for a very long time. Stephen was plugged in with what was going on, and he was a furiously hard worker. I was always locked away, never wanting to play anyone anything, and he was always out there playing everyone things. He introduced me to Alan McGee, which got me the deal for Trashmonk. And after the Dream Academy's tour, I didn't know what to do, and he said, “Will you come on tour and play acoustic guitar opening for me, and play electric in the band as well?” So I did that. And then he made the Duffy record and said, “Will you do the harmony?” And that was that. It's amazing, a great song. He's a great pop writer.

You know, you mentioned how Stephen made a killing from co-writing with Robbie Williams. Just as an observation, I'm sure one could do a lot worse in regards to recurring paydays than having a few co-writes on a Pink Floyd album.

It's… [Starts to laugh.] Well, you know, what sticks in the craw is the pieces I wrote that didn't get on! But that's how it goes. Really, the relationship with David and those guys… Well, as you now know, it's been a very lucky arc since I was about 16 or 17. And it's been a very wonderful thing.