Stay Tuned By Stan Cornyn: Loudest Purple

Every Tuesday and Thursday, former Warner Bros. Records executive and industry insider Stan Cornyn ruminates on the past, present, and future of the music business.

1970 – 1973

Tired of rankings from Billboard and Rolling Stone? Well then, How about a #1 ranking from the Guinness Book of World Records. It was that “all time” encyclopedia that first made an all-time sober judgment on which was The World’s Loudest Band. That judgment was made in 1972, when, at a concert at the London Rainbow Theatre, the performing band’s sound reached 117 dB. And three audience members were rendered unconscious.

This was not a ranking that would change annually, most recently by the Foo Fighters. But I consider it a “most ever” ranking, so you must put it in the same drawer with World’s Tallest Mountain, and which biggest dinosaurs you save.

The World’s Loudest?

Deep Purple

“Purple,” as people in Burbank started calling this English group, showed up at Warner Bros. Records (this is “U.S. market only” here) after a few, early albums got flubbed by the group’s first U.S. distributor, the tiny label Tetragrammaton, a subsidiary start-up label owned by Bill Cosby.

In the late 1960’s, Deep Purple got flubbed by Tetragrammaton. The band’s third album was even delayed by that troubled label until after the band’s 1969 tour ended. Made no marketing sense, but Tetragrammaton went out of business, and its assets sold to Warner Bros. Records, which thus became Deep Purple’s U.S. label through the 1970s. Selling on Deep Purple’s behalf was the band’s English backer and manager, Tony Edwards. He was into music. An ex-clothier, Edwards went to rock concerts wearing a tweed cape and deerstalker hat, a la Sherlock Holmes. Edwards stood out.

Two singles emerged during the months following – “Hush” and “Kentucky Woman” – but without a firm label deal, “That year lost us a year in American,” recalled the group co-manager John Coletta.

Check out “Hush” performed by the Mark I version of the group, within the Playboy Mansion, here:

While all this financial fumbling went on within the labels, the group was fumbling, too. Two musicians within Purple, Jon Lord and Ritchie Blackmore, persuaded (pushed) drummer Paice in a strong direction. Heavy sound. Lord and Blackmore hated being called a “clone of Vanilla Fudge.”

Heavy, loud as we can make it.

With this year of America-at-sea, Deep Purple found itself in Europe. Their single “Black Night” went #1 all over, England, France, and Germany. At a concert in Stuttgart, 4000 fans rioted outside the arena. In Sydney, Deep Purple drew 34,000 to Randwick Stadium, more than the Beatles had.

But American release was on hold.

Paice agreed: “A change had to come. If the rest of the band hadn’t left, the band would have totally disintegrated.” Mark II, the next version of Deep Purple, was ganged together, one that on longer issued albums with title words like “Concerto” and “Suite.” The band’s new descriptors would become words like “Fireball” and “Burn.”

And so, Warners inherited a vanilla-fudge-free Deep Purple, one that blasted amps for years to come.

1970 – Deep Purple in Rock

This second version of Deep Purple, known as Mark II. In it:

Ian Paice – drummer

Jon Lord – organ, keyboards

Ritchie Blackmore – guitar

Roger Glover – bass

Ian Gillan – vocals

The new Purple released a new violence, with Gillan’s howling vocals, Lord’s organ distortions, and a rhythm section as aggressive as World Wrestling Superstars.

Out in 1970, Mark II’s first championship bout was called In Rock, with Mount Rushmore to prove it. Heavy Rock became known as Heavy Metal. To prove it, out came mighty concert tumults like “Speed King,” “Into the Fire,” and “Child in Time.” “Black Knight” was a smash (#2) in Great Britain.

Deep Purple was out front of two other would-be front-runners of Heavy Metal: Led Zeppelin and Black Sabbath. All three groups were defining music that smashed audience’s ears (and all three distributed by WEA).

1971: Fireball

Released in July, 1971, Fireball was a side-step. It did get to #1 in the U.K., but not for long.

The boogie-sounding “Strange Kind of Woman” was featured in the U.S. version of Fireball, which went Gold in America, but not Platinum. Band members were iffy about the LP. Ritchie Blackmore complained “We virtually made everything up in the studio. We were working so hard, we never had time to sit back and think of new ideas.”

Gold is good, but next got better.

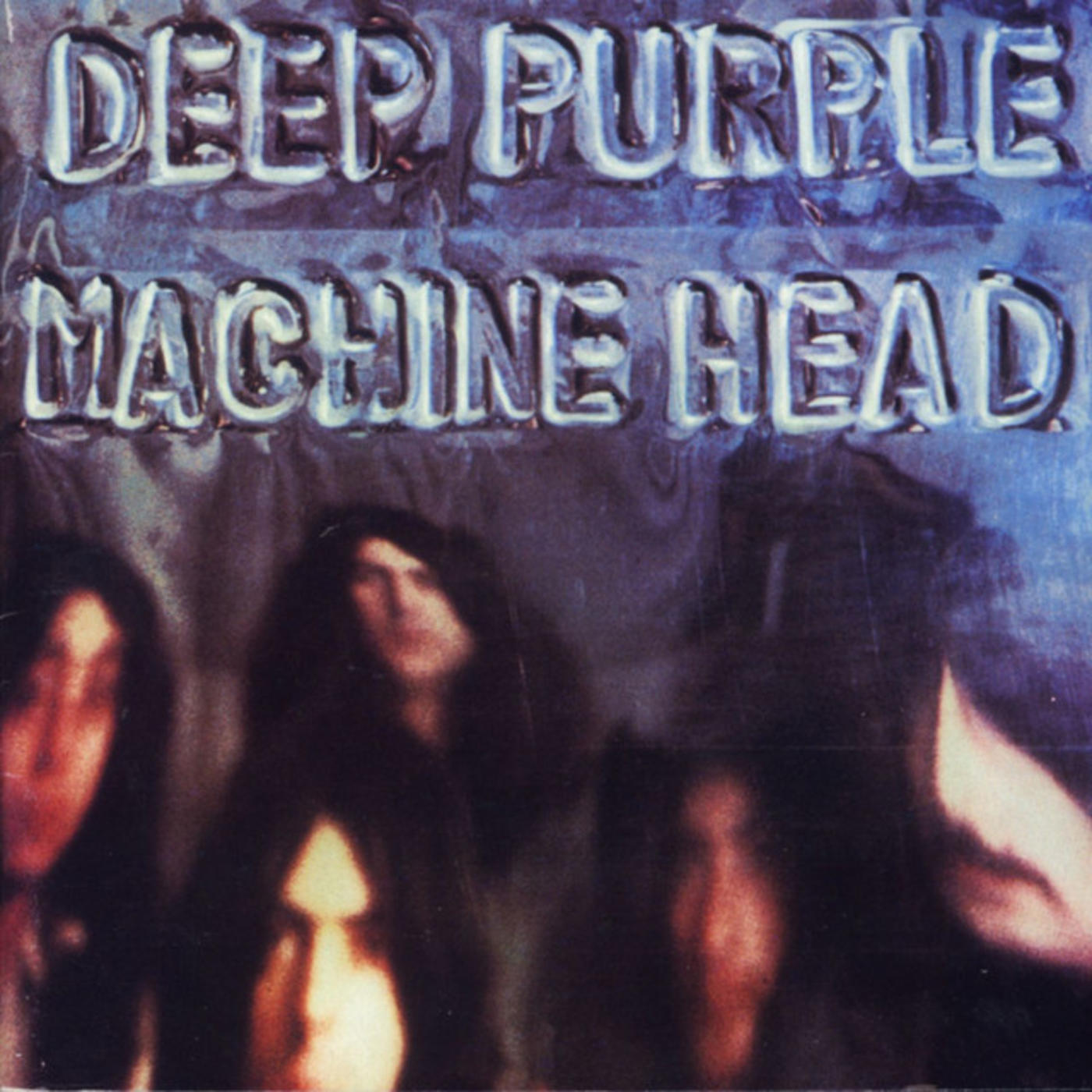

1972: Machine Head

Recorded over in Montreux, Switzerland in late 1971, Machine Head had to handle distractions like its audio studio burning down (after the night before, when a fan tossed a flare into the Montreux Casino’s roof, where the album had been planned to record).

Other buildings were soon found in Montreux. Machine Head met its public in March, 1972. It became Deep Purple’s grrrreatest hit. Once it got on the Billboard 200 chart, it stuck there for 118 weeks, reaching #7 at one point.

One reviewer confessed “The first side is a solid 20 minutes of relentlessly consistent heavy rock, with ‘Never Before’ in particular a great song – a blistering amphetamine guitar riff contrasted by a most effective melodic bridge in the middle of the song...setting up a splendid 20-minute drone of the energetic street-clatter heavy metal fans have come to love so much.”

Metal fans extolled many cuts on Machine Head, including “Smoke on the Water” (the title based on the burn-down of the recording Casino) and “Space Truckin’.”

Relive “Smoke on the Water” by Deep Purple on tour, when you listen in here:

For Deep Purple, it’s back on the road, including a Japan tour where they’d record …

1973: Made in Japan

This release began as just another vinyl album, then a double-vinyl album only for release in Japan, but it ended up an instant and world-wide hit. By now, Deep Purple had racked up sales of over 3,000,000 albums, and Made in Japan had just opened a new door.

The tunes (or “orgies”?) all came from previously released Purple albums. What was different now were those songs were performed live. Like ‘Space Truckin’,’ which in Made in Japan runs 17 minutes, with blistering speed runs, pulsating macho rhythms, and spine-tingling feedback (to quote one review).

To Deep Purple it became evident that, to enjoy their lives, they much preferred performing live concerts over dead recording studios to spend hours in. They are, they knew, a live act. On stage, they got to show off. For this Japan album, three concerts were merged into two LPs.

The album was not designed for “the rest of the world.” Recording of it had been financed by Warner Bros. Records/Japan. It cost the Japan company $3000. No overdubs or studio remakes on it; pure “live.” But when Purple heard it, they knew it was “worldwide” in appeal, and arranged that deal.

In April, 1973, the U.S. version came out. And worldwide, it sold like the devil: it went Platinum in two weeks.

1973 - Who Do We Think We Are

Deep Purple was in over-drive gear. January ’73, they released another album, Who Do We Think We Are, with its single “Woman from Tokyo.” Recording it was stuffed into a European tour in ’72, in Rome, then Frankfurt.

With the release of these albums, Deep Purple again was feeling exhausted. Tourrrrring had got to them. Their managers, Edwards and Coletta, knew that bands don’t stay hot forever, and pushed them out and around.

Later, Ian Gillan recalled it as “We had just come off 18 months of touring, and we’d all had major illnesses at one time or another. Looking back, if they’d have been decent managers, they would have said, ‘All right, stop. I want you to all go on three months’ holiday. I don’t even want you to pick up an instrument.’ But instead, they pushed us to complete the album on time.We should have stopped. I think if we did, Deep Purple would have still been around to this day.”

They also felt, as they had at the beginning of this story, it was once again time to change their sound, this time, as Blackmore put it, they’d “grown to ‘poppy,’ There’s a need to get more bluesy.”

Band members fought, didn’t speak to one another. To finish Who Do We Think We Are, band members had to be scheduled in to record individually, to avoid hassling. In 1973, the group had become the U.S.’ Top-Selling Artists. #1.

Who Do We Think We Are sold half a million copies in the U.S. in its first three months. Airplay took off: “Rat Bat Blue,” “Smooth Dancer,” and “Our Lady.”

But this Heaviest version of Deep Purple, the group-version called the \Mark II, was now disintegrating. Its final concert would take place in Osaka on June 29, 1973.

What next?

Mark III Comes Next

It all felt so out of control now.

Changes within the group, again. Two of them.

Now, even their lead singer, Ian Gillan, wanted out, and after “boxes and boxes” of tapes, Deep Purple found its new voice, David Coverdale.

When David Coverdale first met the group, organist Jon Lord recalled “he was wearing disastrous flares – loon pants, I think they used to call them. He also had this slightly transparent caterpillar on his to lip. I said, ‘There’s only one fucking mustache in this band, and it’s mine!’”

Also guitarist Roger Glover was being replaced by, it turned out, Tommy Bolin.

For Bolin’s audition, the report runs “he walked in, thin as a rake, his hair colored green, yellow, and blue with feathers in it. Slinking along beside him was this stunning Hawaiian girl in a crochet dress with nothing on underneath.

He plugged into four Marshall 100-watt stacks and … the job was his.”

Loud wins.

-- Stay Tuned