Stay Tuned By Stan Cornyn: Rock And Soul

Every Tuesday and Thursday, former Warner Bros. Records executive and industry insider Stan Cornyn ruminates on the past, present, and future of the music business.

Before there was Rock and Roll, there was Soul music that rocked congregations on Sunday, and rocked bars and bungalows night and day.

“Soul” was pop music in the black neighborhoods. Its rhythm is stomp stomp stomp. Its singers would exclaim and scream the words. Its stars on stage would sweat through their shirts and panties.

For white kids (I used to be one), “soul” was a miracle. I’d been raised away from going to church, except what my Auntie Lois (pronounced “Low-ee”) was in town and played a small organ at some services. And we sat still through it all. We only got close to “soul” when we had our own radios, and could listen to some station in some downtown. And they were not broadcasting religious services.

For me, I heard “soul” just after WW2, so call in 1946. Four years earlier, Aretha Franklin was born (March 25, 1942) in a simple house in Memphis, Tennessee, at 406 Lucy Avenue.

1946

What one heard as black/pop records in ’46 was swinging, up-tempo, dance tunes, then referred to as boogie-woogie. Or “jump blues.” A hit that year was Louis Jordan’s “Choo Choo Ch’ Boogie.” (On the white charts you’d have to say was “Peg o’ My Heart” by The Harmonicats. Or groups like the Ink Spots and the Mills Brothers. But not good stomp yet.)

This was before the doo-wop hits of the 1950s.

She was musically lucky, though. From the year of her birth, music was in her life seven days a week, and on Sundays especially, because her father was a preacher-man.

What Aretha Franklin was growing up with was Black Gospel, sung with passion and impact in little neighborhood churches. Aretha’s father had one, and he was the Rev. C.L. Franklin, at the Detroit-based New Bethel Baptist. The Rev. and Aretha’s mother Barbara separated in 1948 when Aretha was but six. Aretha lived with the Rev., who got known for emotion-driven sermons by “the man with the million-dollar voice.” He even sold recordings of his sermons.

Aretha’s mother died in 1952, and Aretha, age 10, began singing solos at her father’s New Bethel church. Her first solo: “Jesus, Be a Fence Around Me.”

Four years later, in 1955, Aretha, age 13, gave birth to her first child Clarence; then at age 14, to her second son, Edward. Father’s name never revealed.

Aretha’s father, C.L., began managing her career, taking her on the road for his “gospel caravan,” performing at churches. Small record deals followed with gospel labels. Aretha toured as opportunities came her way. On one tour, she fell for Sam Cooke, singing with his gospel group the Soul Stirrers.

Aretha tuned in to her favorite of the ‘50s, Dinah Washington.

Sam and Aretha both wanted “secular” recording careers.

The Big Time

By 1960, Aretha’s father produced a two-sides demo for Columbia Records, and she was signed. Her first single there, “Today I Sung the Blues,” went Top Ten on what was then called the Hot Rhythm & Blues chart.

But Aretha’s years (1961 to 1967) wavered, leaning to “pop.” She recorded 10 albums for Columbia, show tunes, jazz, pop, R&B. Aretha’s gospel background was not where Columbia wanted to go with Aretha. Columbia wanted her to sing for the big pop market.

In 1963, Columbia had even run an ad with the headline “Can Gospel Replace the Twist?” Another attempt at enlarging its audiences.

In 1966, appearing at Philadelphia’s Cadillac Club, Atlantic Records’ Jerry Wexler walked in. He’d been keeping track of her for years.

Contract up with Columbia, Aretha, now 26, had met the world, its men, its hot times, and some good money.

1967: Aretha Sails Across Atlantic

That January, Aretha chose to sign with Atlantic, largely because Jerry Wexler made her feel right. Wexler bonded with her. He told her he’d been a fan since he heard her first album, Songs of Faith, recorded for her father when she was just 14. He even knew the song in it: “Precious Lord,” recorded in the Rev. Franklin’s church.

He invited her up to his home, and together they listened to possible records. Aretha loved that music had become #1 at Atlantic, at least with Mr. Wexler. Wexler was in awe of her voice, its power, like a jet engine that’s ready to take off.

Wexler talked about recording. How he liked it better down south, in Memphis and beyond, about his Stax deal for Sam and Dave there. And with Ray Charles. How like Ray, she was a “hands-on performer,” turning church rhythms and her two-fisted piano playing into Holy Ghost power. Good stories.

He even told Aretha about a party he’d just gone to at Frank Sinatra’s New York floor, and how Mr. Sinatra had put his arm around him and asked if, maybe, he might be able to sing a duet with Aretha Franklin? (Slightly exaggerating, Wexler mentioned how that felt: he’d just about wet his pants.)

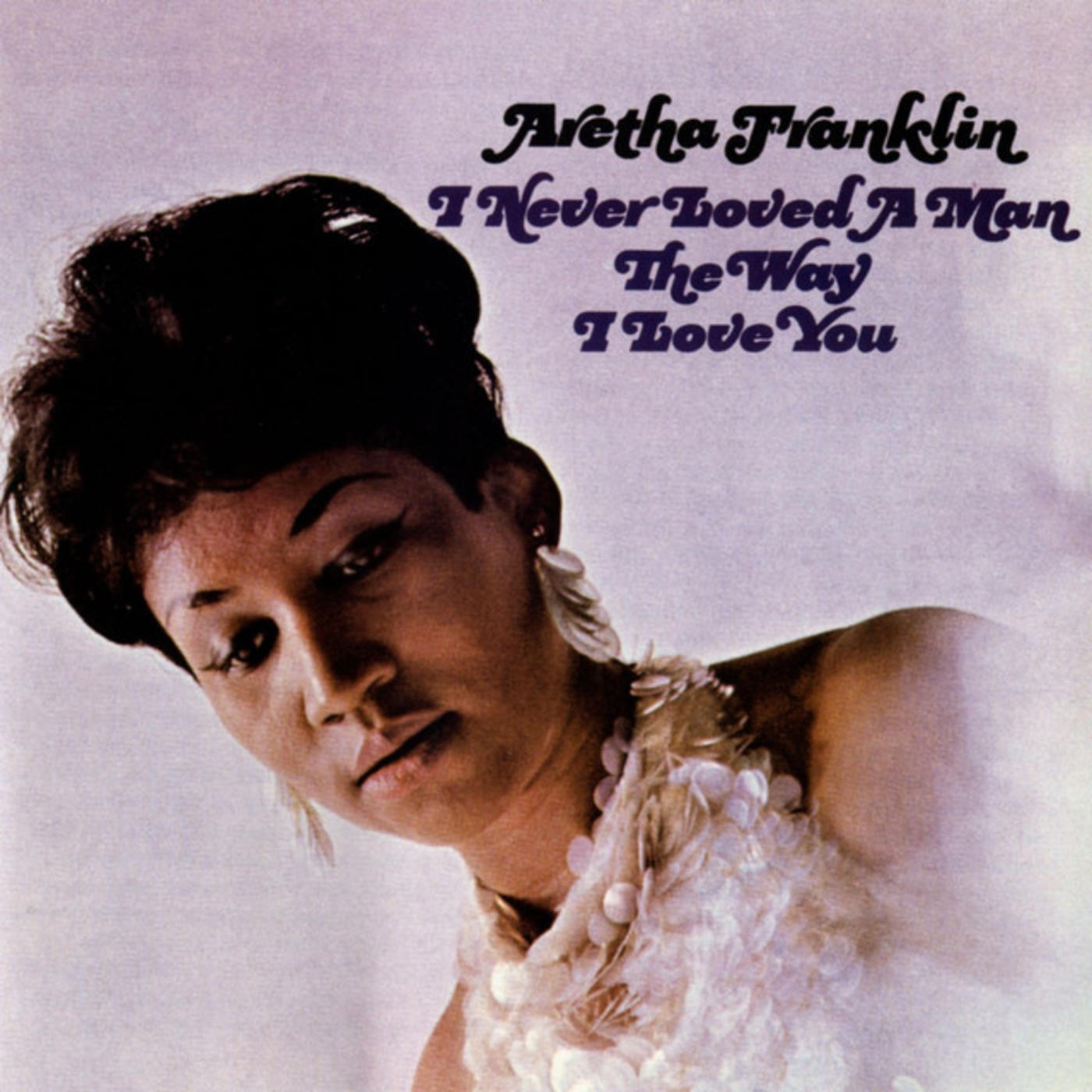

Time came for Aretha’s first recordings, and they’d decided on the FAME studios in Muscle Shoals, where they’d work with the Muscle Shoals Rhythm Section; white boys. The A-side was set: “I Never Loved a Man (The Way I Love You).”

I guess I'm uptight

And I'm stuck like glue

Cause I ain't never

I ain't never, I ain't never, no, no (loved a man)

(The way that I, I love you)

In the session, they got that A-side perfect, but argument within the band – a racial dispute that included gun shots – left the Muscle Shoals cancelled, Atlantic with only half a B-Side. That got finished up in New York: “Do Right Woman, Do Right Man” Out that February, and it got to #1 on the R&B chart.

If you wanna do right all days, woman

You've gotta be a do right all night, man

April: Next single was “Respect,” an Otis Redding masterpiece which made it to #1 not only on the R&B chart but on the Pop chart, too. She and her sisters sang on it, adding the “sock it to me” line, especially appealing to women with an urge.

R-E-S-P-E-C-T

Find out what it means to me

R-E-S-P-E-C-T

Take care, TCB

Oh (sock it to me, sock it to me,

sock it to me, sock it to me)

A little respect (sock it to me, sock it to me,

sock it to me, sock it to me)

Whoa, babe (just a little bit)

Then both #1 singles in one album.

The singles stayed hot. In 1967-68, Aretha gave Atlantic six Top Ten singles, five of them certified platinum.

Million sellers all. Followed by a live performance at the Fillmore West, with a special moment caught on tape. Ray Charles recalls, “I happened to be in San Francisco, and someone said Aretha was performing. Well, far as I’m concerned, she’s the right one, baby. I’m not much for hanging out, but I will go to see Aretha. She’s my one and only sister. So I get to the Fillmore and I sit way in the back, trying to be inconspicuous and not bother no one, when all of a sudden someone spots me and next thing I know Aretha’s come to get me talkin’ ‘bout ‘I discovered Ray Charles!’”

And up on stage, they sang and played as two souls from different pages of the Atlantic calendar, tonight merged together. Wexler recorded it, just sitting out front. He wept.

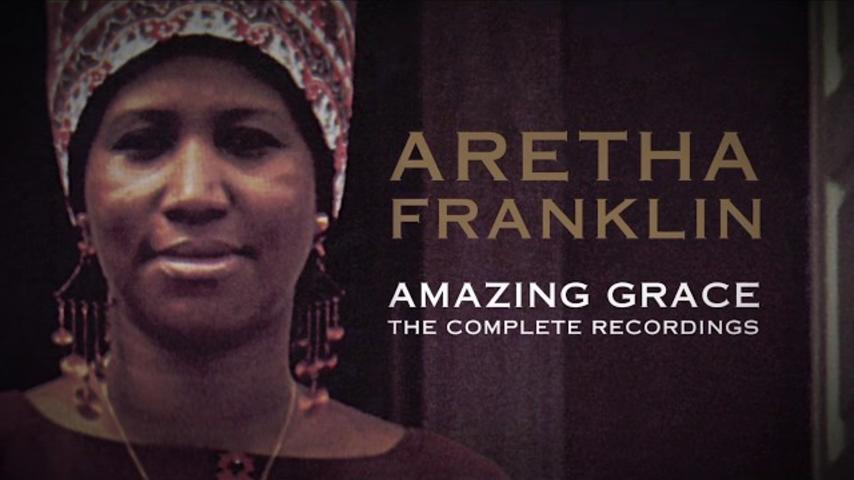

“Amazing Grace”

Albums sold like singles. This one in particular:

Amazing Grace, her 1972 return to gospel, recorded at the New Temple Missionary Baptist Church in Los Angeles during January. It featured not only Aretha but also her father, C.L. Franklin, and is filled with moans, gliding pitches, and wails coming from gospel in church.

Aretha simplified the melody and lyrics of the title song to two stanzas, then stretches that into an 11-minute performance.

The song had been a standard to perform within and out of churches for hundreds of years. Starting in 1971, the title song had become an anthem for resistance to evils. Earlier performers of the song (there’d been hundreds of them) ranged from Judy Collins’ in her Whales and Nightingales, to the Royal Scots Dragoon Guards playing bagpipes. This became Aretha’s biggest seller of all time, selling over two million copies.

But with Jerry Wexler gone from Atlantic (to Warner Bros. Records), fervor was less. Aretha now worked with Curtis Mayfield in the Wexler chair, and one more single hit the charts: “Something He Can Feel.”

But in 1979, it all seemed to have changed. Her father, Rev. C.L., was shot in his fight against robbers at his home in Detroit. (He remained in a coma for five years, and died in a nursing home in 1984.)

Also changed that year: Aretha signed with Clive Davis’ Arista Records. There, her career moved on for 20 more years, though admittedly with less passion than the Atlantic era.

In 1985, the Michigan government decreed her voice “a natural resource.”

Aretha Franklin had become an icon. She lived intensely. One count was that she smoked 10 packs of cigarettes a day. That means 200 cigarettes a day. Which amounts to one new cigarette every five waking minutes.

She either ate or dieted, again and then over again. “Yo-yo dieting,” she called it. She could do as she pleased. Including drinking.

In January of 2009, she sang “My Country ‘Tis of Thee” at President Obama’s inauguration. She wore her church hat.

Soul without end.

-- Stay Tuned